The Counter: Vermont law banning food waste leads to more compost—and “separation” anxiety

/Take a moment to read this article by Katherine Cusumano, recently published by The Counter: Vermont law banning food waste leads to more compost—and “separation” anxiety.

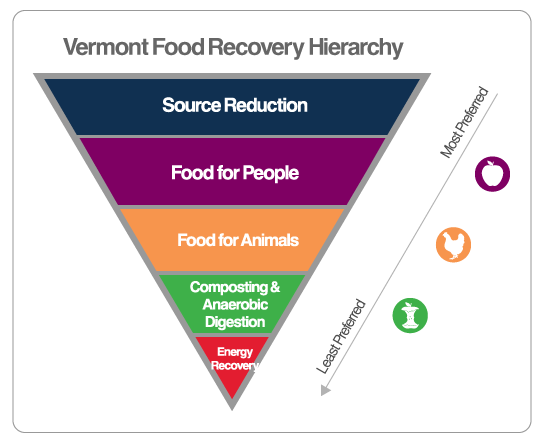

It provides an overview of Vermont’s Universal Recycling Law, Act 148, and describes how the law is unique in establishing a “food recovery hierarchy”.

The law dictates that highest priority be given to food recovery, ideally as donations to feed people. If food is past it’s prime, then priority is given to turning it into feed for animals. Next in the hierarchy is composting or anaerobic digestions. Last and least preferred is energy recovery.

““What was really interesting about Vermont’s strategy was thinking about it from a systems perspective—not just the fact that they wanted to get the food out of the landfill, but also how to make sure that it’s not getting wasted in the first place.”

—Laurie Beyranevand, a food policy expert and the director of the Center for Agriculture and Food Systems at Vermont Law School

The article shines light on the importance of source separation in food scrap recycling and highlights the challenges many VT composting businesses like ours now face as the hierarchy is loosely interpreted and challenged.

The article features remarks from Tom Gilbert of Black Dirt Farm, Karl Hammer from Vermont Compost, Natasha Duarte of Composting of Vermont, Phil Carter of Ludlow Community Garden, and Caroline Gordon of Rural Vermont, among others.

“One essential component of clean compost is source separation, which the law defines as separating organic and recyclable materials from non-recyclable, non-compostable materials at the point where waste is generated.

But some Vermont farmers and advocacy groups say that ANR has not upheld this definition of source separation. As a result, they say, the agency has favored large commercial haulers over farmer-composters. In 2018, the agency granted a permit to AgriCycle, a Maine-based hauler that takes loads of both packaged and unpackaged food waste to depackaging facilities; earlier this year, a depackager operated by the waste-management behemoth Casella came online in Vermont. Gilbert, of Black Dirt, and Karl Hammer of Vermont Compost Company both say such haulers have siphoned business away from their farms—and, they say, depackagers introduce pollutants that farmers had worked for years with waste generators to remedy. “Plastic contamination has always been one of the biggest challenges to the integrity of the compost,” Hammer said.”

Read the full article here.